Supervisors Ignore Their Own Policy and Fail to Require Affordable Housing

Despite requirement to include affordable housing in projects, Supervisors fail to take action, approving high end housing that will contribute to the affordability problem in San Diego County.

Supervisors Ignore Their Own Policy and Fail to Require Affordable Housing

Despite requirement to include affordable housing in projects, Supervisors fail to take action, approving high end housing that will contribute to the affordability problem in San Diego County.

On Wednesday, July 25th, the Board of Supervisors ignored their own policy requiring development projects include an affordable housing element whenever a major change in zoning (a General Plan Amendment) is requested. This was the first of the hearings to use a controversial tactic known as GPA bundling to approve multiple general plan amendments at one time rather than one at a time as is usually the case with large controversial projects. They did this in order to rush through 8 projects this year, more than the four allowed by state law. Bundling effectively limits public input by increasing the burden on the public to participate in hearings, particularly controversial ones where the public is concerned about their safety and well-being. And, importantly, they shirked their duty that would have helped alleviate our housing crisis and instead, they are actually contributing to higher housing costs in the region.

(revised 8/15 for clarity and accuracy)

Affordable housing is required.

The County of San Diego’s General Plan (GP) includes several policies that are intended to increase the production of affordable housing. The goals and policies component of the GP Housing Element identifies “Affordable Housing through General Plan Amendments” as a policy to meet the range of housing needs for County residents. The policy (H-1.9) requires that developers provide an affordable housing component whenever a large scale residential project is proposed as a GPA.

In the City of San Diego, developers are automatically required to include an inclusionary housing element where upwards of 20% of the units are deed-restricted to be affordable to the moderate, low or very low income households. This means that the housing prices would be pegged to be a percentage of the median income for the area. The county General Plan, likewise, requires an affordable element. But the Supervisors are choosing to ignore it, at their peril.

Missed opportunity

On July 25th, when the supervisors voted to approve the three bundled projects (3500+ homes), they should have required 20% of the housing be set aside as housing for moderate income households, which would have yielded 700 more houses to County inventory that a median income household could afford. Instead they green-lit 3500 market rate homes that would effectively increase the average cost of housing in San Diego County. Grow the San Diego Way presented a compelling presentation showing that the houses being proposed would, in fact, increase the cost of housing and not address the main issue we are facing, namely that the median area income households cannot afford to live here. They had an opportunity to do something about the housing affordability crisis and purposefully chose not to do anything.

H2.2 Affordable Housing through General Plan Amendments. Require developers to provide an affordable housing component when requesting a General Plan amendment for a large scale residential project when this is legally permissible. (San Diego County General Plan, A plan for Growth, Conservation and Sustainability), Adopted August 2011) P6-13

What’s the big deal?

The Board of Supervisors is tasked with approving large-scale changes to the general plan (known as General Plan Amendments), which are often controversial because they set aside the recently approved general plan (which is a consensus-based “constitution” for land use that the County spent $18 million and 13 years developing). The GP was approved only a few years ago. To justify a GPA, there is a high threshold, namely that the change is “in the public interest” and that it is not “detrimental to public safety or welfare.”

The two projects located in North County—Harmony Grove Village South and Valiano—were proposed by developers and their out-of-town investors who speculated on cheap land knowing that it was not zoned for the type of intensive uses that they had in mind. This area of North County, located in a rural valley surrounded by thousands of acres of permanently preserved open space chaparral and coastal sage scrub habitat, has had significant wildfires on average every two years or so since the eighties, including, most recently, Coco’s Fire which destroyed 40 structures. For this reason, the General Plan specifically zoned it for lower density because the two lane road serving the valley cannot accommodate the kind of evacuation traffic that higher density housing would bring. The General Plan of San Diego policy LU-6.11 specifically mentions protection from wildfire:

Despite the clear danger of placing more density in this valley, the developers pushed forward knowing that the Supervisors, who are the ultimate arbiters of zoning changes, would rubber stamp any project under the guise of “we need more housing.” In order to do so, they would need to show a) a justification that it is in the public interest and b) that it would not be detrimental to public health, safety or welfare.

The second point was addressed very succinctly by the community and in this white paper, written by contributor and Harmony Grove resident, Erin Dummer. In it, she puts forth the clearest arguments possible for why Harmony Grove Village South (and Valiano) are clearly detrimental to public safety and welfare. Forthcoming lawsuits will have the courts likely siding with the community in the “very high fire hazard severity” zone as they have done recently, elsewhere in the state.

The real question is, is it in the public interest? The developers argue that the housing crisis dictates we should set aside the pesky general plan to address the shortage we are facing.

LU-6.11 Protection from Wildfires and Unmitigable Hazards. Assign land uses and densities in a manner that minimizes development in extreme, very high and high fire threat areas or other unmitigable hazardous areas.(San Diego County General Plan, A plan for Growth, Conservation and Sustainability), Adopted August 2011) P3-26

Any proposed amendment will be reviewed to ensure that the change is in the public interest and would not be detrimental to public health, safety, and welfare.” (San Diego County General Plan, A plan for Growth, Conservation and Sustainability), Adopted August 2011) P1-15

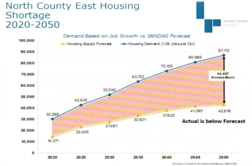

The nature of the housing crisis: it is a shortage in the moderate and low end

If we have a crisis, then we should understand it fully and determine what, empirically, can we do to address it. According the latest Regional Housing Needs Assessment (RHNA) mid-cycle report, we are producing only half as much housing as we should be producing. In fact, for the past several 10 year cycles, we have not produced enough housing to meet the regional need. However, what this clear fact obscures is that the type of housing we are short on is specifically in the “moderate income” and lower bracket. In the County of San Diego, the RHNA reports have consistently shown that we are over-delivering “above moderate” housing (e.g. high end homes and condos) to the detriment of the moderate and lower income housing. In the last complete cycle, we delivered 152% of the “above moderate” and only 20% of the “moderate and lower.” Housing costs continued to climb throughout that period.

In the current cycle, we have fallen even further behind in the “moderate,” “low” and “very low” categories which are now at 14% of where they should be at this point in the cycle (figure 2). It is at that level of the housing market where there is a shortage and thus, the most competition. What this tells us is, while housing production is not where it needs to be, the deficit is exclusively in the “moderate income” and lower housing segments and that is where competition is highest.

This is important because, as you’ll see below, the projects that are being proposed (specifically, Harmony Grove Village South and Valiano) have average costs that are $670,000 and $770,000 respectively for the close to 900 homes being proposed, way in excess of the median house value in the County.

________

There is a severe lack of supply in the moderately priced and lower levels of our housing market while the upper income bracket properties are fully stocked. This creates upward price pressures from the low end, where prices are rising fastest, not the high end.

________

This imbalance shows up in the local real estate market with a tighter market on the low end while the high end softens.

Realtors in North County have already noted that the high end is softening. Looking at the San Diego housing market overall, most recent figures (June 2018) show that sales have increased year over year in the higher end; the higher the value, the more the sales have increased. This means that higher value homes are selling more than they did last year at the same time (an increase of 7%). Housing sales in the sub-$500K range, on the other hand, have decreased significantly from last year (dropping 22% from last June). This is due to the dearth of production of Moderate and Lower income level housing. And, not unsurprisingly, this is the only housing that the average San Diego resident can actually afford. The only housing that is being built is high end housing, despite the fact that it is middle and lower end housing that we desperately need. Figure 3 shows year-over-year sales increases in the high end and severe declines in the low end. Further reinforcing this point, the time on market for high end housing is longer (average of 36 days) while, for the lower end housing it averages only 29 days. What this points to is a clear softening of the high end and a tightening on the low end due to the over-supply of the former and under-supply of the latter.

And the rental market in San Diego County fares no better. According to MarketPointe Realty Advisors, a glut of high end rentals is starting to hit the market and the vacancy rate has hit the highest point since 2014: 4.08%. Average rents have hit close to $1,900 per month. However, the most telling figure is that for moderate or lower income apartments ($1,200 per month or less), the vacancy rate is about half, at 2% due to lack of supply.

How about similar North County developments?

We can look at specific projects in North County to see how well they’re selling and at what price points. Since the two GPA projects in North County are immediately adjacent to an existing project in build-out phase (Harmony Grove Village) that is about 40% complete, we can look to that project for some data on the market for recently-built, high end housing.

Over the past 12 months, the average sale price for HGV was $668,032 (based on MLS data). 56 homes were listed, 22 were sold. They averaged 2,254 square feet of living space. Interestingly, these houses spent an average of 42 days on market which is almost twice as long as other housing in that price range. That means it is taking longer to sell homes in HGV than in the rest of the County for similarly priced houses. HGV was approved in 2007 and broke ground in 2014. They are approved for 742 homes. Only about 300 have been sold. As the media and the building industry have focused so intensely on the dire nature of our housing crisis, one would think that these houses should have been sold by now. In fact, the developer, Lennar, has lowered prices to entice more sales, according to frustrated residents who purchased prior to the price drop.

It is in this context that two developers would like to place close to 900 homes of similar size and design (small lots, clustered) despite clear evidence that this type of housing is not moving very quickly.

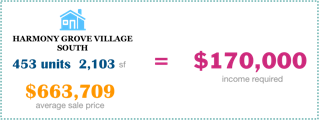

The Harmony Grove Village South project features 453 units across five housing products ranging in size from 800 square feet to 3,000 square feet, with the majority being above 2,100 square feet. Again, using the existing sales at Harmony Grove Village, these homes will conservatively fetch in the $664K range. The pricing model underestimates cost per square foot for smaller units so the housing costs will likely be higher. Needless to say, this will not be affordable to the median family household income of San Diego county ($82K) nor the local area ($62K per year in the I78 North County market area). You would need to make $170,000 per year to afford this type of housing, if you include the HOA fees (average of $300 in SD County) and Mello Roos which will likely come in at $200 - $300 per month range, which is what HG Village residents are paying. Even the handful of studios they are offering in this project will be unaffordable to the median income. Given that the median home value countywide is $575,000, this project will actually increase the average cost of housing in the area as it will be about $100K higher than the median priced home.

Based on Newland Sierra’s own market analysis, conducted in 2016 by MarketPointe Advisors, the average Newland Sierra home would cost $548,000 (in 2016) which, not coincidentally, matches the average cost of the detached single family home for the market areas in their analysis. However, this figure does not take into account the fact that the market has increased significantly by almost 20% since 2015. So in actuality, the average cost for a Newland Sierra unit would be around $658,000 which is in line with the average single family home cost countywide ($660,000).

But, high end housing will free up lower end housing for the poor, right?

One theory that has been floated out there by various BIA-sponsored economists and parroted uncritically by the media is that if you build more high end homes, then the wealthier home buyers won’t “slum it” in the low end because there’ll be plenty of high end housing to choose from.

Conveniently ignored in this assumption is that there is virtually no data supporting this. And they dismiss any mechanisms that might make housing more affordable on the low end (e.g. subsidies, inclusionary requirements, land trusts or other interventions).

The market will provide and don’t even think about other potential tools to help increase affordability. Building a glut of high end housing will somehow magically provide the massive amounts of moderate and lower income housing that we desperately need. Looking to the building industry for solutions to the housing crisis is like looking to the fox for solutions on how best to guard the henhouse. The industry’s overall profitability is directly linked to the high cost of housing so they have no incentive to “build our way to affordability.”

What evidence is there?

Earlier this year, economists at the Federal Reserve Bank developed an econometric model to try to answer the question of whether more high end housing would lower housing prices. The Fed had to create a simulation model because there is no data that answers that question; “there are no direct estimates of the rent elasticity with respect to new housing supply in the literature.” Their findings? A 5% increase in supply of high end housing had a statistically insignificant impact on housing costs (.05%). In other words, building 75,000 more houses in San Diego County would only lower prices by .05% which is basically a rounding error. The Fed, hardly an “anti-growth” entity here is arguing that supply has a marginal impact on housing costs. That is because the cost of housing has more to do with the amenities (desirability) than it has to do with the supply. Sure supply is important, but it is supply on all affordability levels not just the high end and ultimately, there are always people willing to pay more to live in a nicer area. Particularly in San Diego and other coastal areas of California, the desirability of living here is extremely high.

Another analysis of the rental market going back 30 years, conducted by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, showed that rent inflation is highest in the lower income categories compared to the upper income categories. This means that the higher average rents we are seeing nationwide are being driven more by inflation of the lower income rentals which is likely due to the reduced supply of that type of housing and excess in the upper end. The Washington Post recently published a piece focusing on how all the high end housing being built has had the effect of reducing the cost of housing for the high end houses and apartments, but the low end continues to become more expensive.

And looking at hot markets similar to San Diego that have over-produced, like Vancouver, BC, over-production doesn’t seem to have had the intended effect of reducing prices. While their population has grown 9 percent over the past decade, their housing growth has been 12 percent and yet they continue to see price increases across the board.

Clearly a combination of market-rate and subsidized housing are needed, but the BIA and its mouthpieces are doubling down on the market-rate portion of this equation while minimizing the other part of the equation. The displacement that is occurring of low income households is exacerbated by market-rate housing in the absence of any moderate or lower income housing production. Research by the Institute of Governmental study shows that:

This means that interventions to assist low income people to be able to afford housing are twice as effective as building high end, market-rate housing.

“If you deny 2,000 high-income families the new housing they want, guess what, they are going to go down the street and outbid your cherished working-class family and take their housing units,” [Beacon Economics’ Thornberg said] said. “You can’t win by not building at the high end.” (Special report: Can we build our way out of the housing crisis?), SD Union Tribune, 12/4/2017

“we’re not going to be able to subsidize our way out of it,” said Matt Adams, vice president of the San Diego County Building Industry Association. “We’ve got to build our way out of it.” (Special report: Can we build our way out of the housing crisis?), SD Union Tribune, 12/4/2017

“through our analysis, we found that both market-rate and subsidized housing development can reduce displacement pressures, but subsidized housing is twice as effective as market-rate development at the regional level” (Housing Production, Filtering and Displacement: Untangling the Relationships), Institute of Governmental Studies, June 2016

But, won’t the high end homes filter down to the lower income people as they age?

Filtering is another popular term in the BIA literature. Filtering is the phenomenon that, as housing ages, it loses value so the luxury housing of today will eventually become housing for the less well off of tomorrow. The biggest problem with filtering is that the process is so slow that it is outpaced by job and population growth and would not begin having an impact until after several decades. A study by the prestigious American Economic Review show that for owner-occupied housing, homes lose their value at the rate of .05% per year which means these homes will take decades to become affordable if they don’t deteriorate beyond viability before that.

So what should we do?

The building industry would like us to believe that to solve the housing (affordability) crisis, we need to build more market-rate housing. While, clearly more housing is needed, the building industry desperately wants us to believe that building market-rate unsubsidized housing will solve the problem. Of course, it is the high value of housing that drives industry profit so it would be highly unusual for an industry to be promoting something that is clearly not in its best interest. When housing prices rise, industry profits rise. When they fall, industry profits fall. Just look at Lennar’s stock prices and they’ve tracked almost to the month, housing prices for the pasts 18 years. So, we should take their prescriptions at face value.

Real annual filtering rates are faster for rental housing (2.5 percent) than owner-occupied (0.5 percent), vary inversely with the income elasticity of demand and house price inflation, and are sensitive to tenure transitions as homes age. (Are Private Markets and Filtering a Viable Source of Low-Income Housing?), American Economic Review, Feb. 2014

For almost 2 decades, we have only met about 17% of the need for moderate income or lower income housing while we have over-delivered on “above moderate” housing consistently. The logical conclusion would be that we need more moderate and lower income housing not more “above moderate” (high end housing) that we are proposing. The building industry is on record opposing virtually any mechanism that might introduce more moderate or lower income housing with the veiled threat that it will drive developers to stop building. They oppose it because it is against their interests, not out of altruism.

What needs to happen is our Board of Supervisors needs to stop approving sprawl projects that destroy the quality of life, environment, put people in harm’s way and importantly actually contribute to the high cost of housing in the region. They should encourage infill projects, near transit, near jobs and away from fire danger. They and the compliant media need to stop letting the Building Industry dictate the conversation and look at ALL ways to address the problem using a combination of market-rate production, incentives, subsidized housing, rent stabilization and land grant programs.

In the next few months we’ll be exploring ideas that could help address our housing situation such as:

In Summary

Will these projects help our housing affordability crisis?

The big question the Supervisors need to ask when approving GPA projects is: “are these projects going to materially improve affordability of housing in San Diego County?” If the answer is no, then there is effectively no public benefit and no reasonable case to amend the General Plan. There is especially no reason to put houses in harm’s way, destroy a rural community and impact the surrounding area with traffic, fire hazards and other effects that the General Plan specifically was meant to avoid.

At the various hearings, the developers’ very detailed presentations focused on the housing need in North County and the proximity to employment that these projects would supposedly provide. They brought in BIA economists (such as Gary London) who gave a detailed breakdown of the housing need in North County. The crux of their argument was that we have a shortage of housing. These projects are close to employment centers and the cost of housing is driving people to commute from further and further away. Hence, we need to be building more housing of any and all types. What is most glaring, however, is that despite the excruciatingly detailed analysis provided by the BIA’s Gary London and his partner Nathan Moeder, they make absolutely no reference to housing affordability by income level. They conveniently avoid any reference to the over-supply of high end housing and the dearth of moderate income or lower housing even though this is how the County, SANDAG and the State of California measure housing need. It is the entire basis for the Regional Housing Needs Assessment and they ignore it completely. This is crucial because in order for the housing market to be healthy we need to deliver housing at all levels of affordability, not just the high end.

Ironically, the developers and their BIA or Chamber of Commerce partners send a call out to their membership base to show up at the hearings to give public comments focusing exclusively on the emotional issue of affordability, because that is where they think they can impact the decision-makers the most. One recent commenter at a Planning Commission hearing, Debra Rosen, who turned out to be the CEO of the San Diego North Chamber of Commerce, a prominent Building Industry Association ally, declared dramatically, with tears in her eyes, “I lost my daughter at 25 years old,” Rosen said. “And I lost her to Idaho. It was really hard. When she left, I said to her, ‘I will help you with the down payment,’ and she said, ‘You can give me a down payment but I can’t afford the mortgage.’ And it’s because there’s not enough homes for sale here.”

These comments were clearly intended to counter the rather emotional testimony of residents whose safety would be jeopardized by these backcountry projects in “very high fire hazard severity zones” with the very real prospect of entrapment during wildfire evacuations that these projects do not account for. There were numerous others with similar stories which echoed the same talking points from the failed Measure B initiative which featured emotional videos of parents whose children couldn’t afford to live here. Measure B was a developer-funded initiative that attempted to trick voters into approving a back country sprawl project under the guise of “affordable housing.” It lost two to one. Despite being overwhelmingly rejected by voters, that same project, Lilac Hills Ranch, is going in front the Supervisors again in the fall.

To answer the question of whether the projects will address the housing affordability crisis, we have to look at two pieces of data which the BIA analysis conveniently ignores. The first, and most important question, is: “what will the average cost of this housing be and will it be affordable to area residents.” The answer to that question is a resounding “no.” Neither San Diego County residents nor North County residents in the I78 Corridor (relatively closer to these two projects) will be able to afford the average house at either Valiano or HGVS and neither will Ms. Rosen’s daughter.

So how much will these houses cost?

In the case of these two projects, Harmony Grove Village South and Valiano, the developers have not been very transparent about what the houses will sell for. They have not conducted a market analysis; they have not given ranges or pricing breakdowns. Newland Sierra did perform a a market analysis back in 2016 which massively overestimated what people can afford. And the market data is now out of date, but it still can give us some direction.

The developers talk in vague terms about the product types and sizes of the housing they will be providing, yet they continuously claim it will help provide housing for the local workforce. Fortunately, they do have some marketing materials, a tentative map, EIR and a parcel by parcel breakdown of lot size and other information from which we can piece together a reasonable estimation of the average home size and with that, based on local area comps for newly built homes, we can estimate the average cost of the housing. Newland actually hired a company to do a market analysis back in 2016, so there is a little more insight into housing costs there.

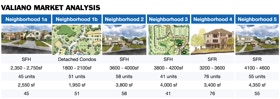

According to the developer’s presentation, the Valiano project features 326 units ranging in size from 1,800 square feet to 4,600 square feet. The majority of the units are above 3,000 square feet. Based on the existing sales of Harmony Grove Village, these home will likely fetch in the $770K range. Needless to say, this will not be affordable to the median family household income of San Diego county ($82K) nor the local area ($62K per year in the I78 North County market area). A family of four would need to earn $191,000 a year to afford this type of housing with 5% down, HOA fees (average of $300 in SD County) and Mello Roos which will likely come in at $500 per month. Effectively, they are creating housing that only higher income people will be able to afford. The “local workers” that the developers suggest will be served by this much-needed housing will still have to commute to Riverside if they want housing that they can afford (or they’ll need to triple their income. So, consequently, it will not be affordable to most and therefore does not provide the public benefit they are saying it will provide.

Notes

Copyright 2020, Grow the San Diego Way