Will housing in San Diego ever be affordable to moderate or lower income households?

A recent article in the OC register, Southern California builders are cutting prices to move glut of unsold homes1 highlights something we’ve been seeing for the past 12 months or so in the San Diego area: a slowdown in sales of newly built (market rate) homes is driving developers to cut prices and slow construction all over Southern California. Yet prices do not seem to be coming down appreciably… yet.

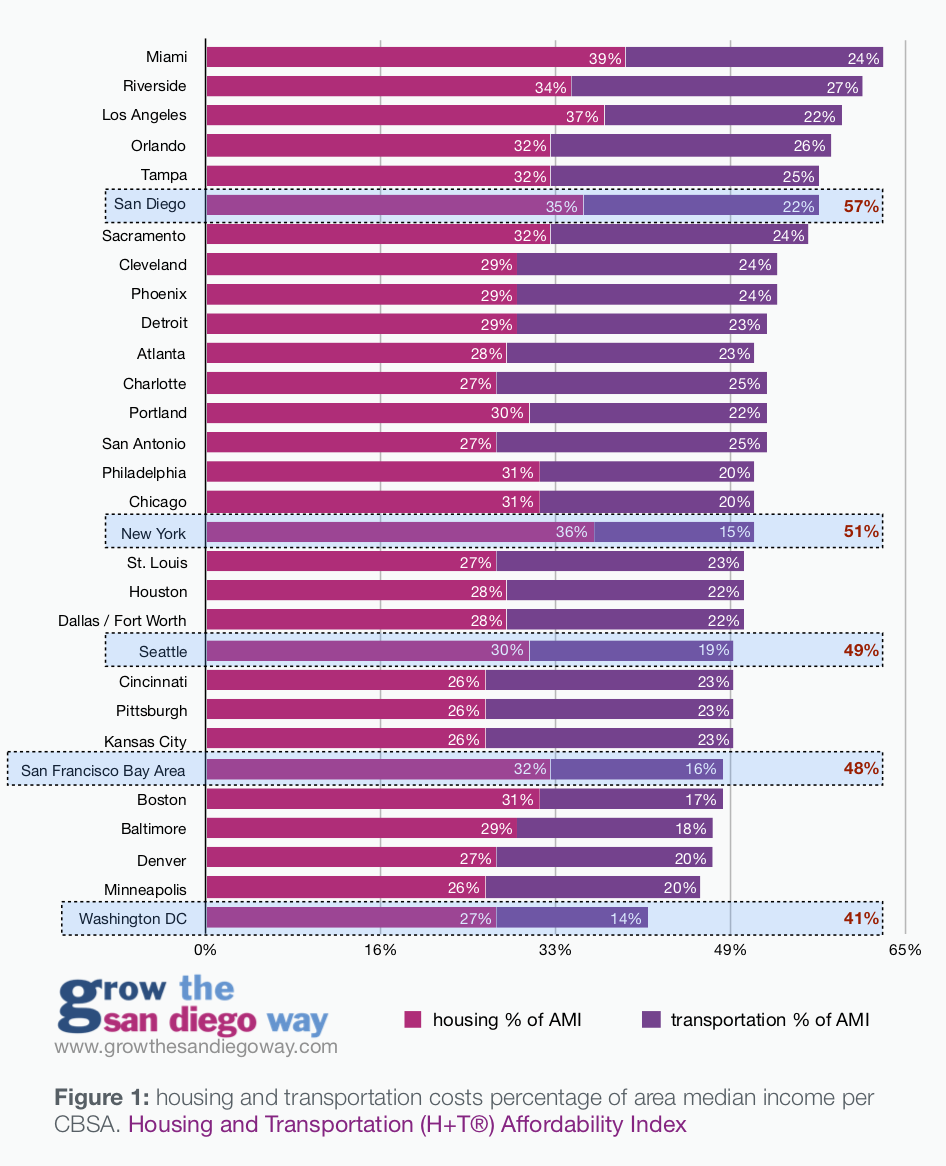

It is important to note that the statewide (and nationwide) housing crisis is as much a result of wage stagnation over the last 30 years as it is related to lack of supply if not more so. Housing costs have increased significantly since 1980 while median wages have barely budged.2 Building housing that the average household can afford might not even be possible, and market rate housing has become truly out of reach for 80% of the households in San Diego.

The incentive for developers to build housing that the average household can afford is low because just the materials and labor (including fees) that go into building a new home — and that’s without the cost of land, marketing or selling the properties — is already higher than many households can afford, at least in coastal California. For the typical San Diego family to comfortably afford a home, it would need to cost about $339,545 (based on median household income of $81,8003 using Zillow’s Affordability Calculator, assuming 5% down, $250 in debt and no HOA or Mello Roos). For households in the “Low” income category (80% of AMI) they could afford $260,994. According to the National Association of Homebuilders, the average cost to build an average home in 2017 nationally was $237,000. That does not include the land costs, marketing, sales commissions or profit and of course is based on nationwide averages. Labor and material costs (and regulations) in California are higher. So it is not likely that developers can’t even build homes that are affordable to the average San Diego household. And of course, why would they, if there are people willing to pay top dollar for housing. So why are we insisting that by building more market rate homes, the cost of housing will somehow come down to reach affordability for all? Developers are in the business to make profit and even a modestly profitable home will exceed the affordability threshold.

Homebuilders target higher end homes (single and multi-family) that are more profitable and will attract higher income buyers who are seeking larger homes and more bells and whistles. This includes higher end finishes like marble and “smart home” features which drives up the cost of the home and makes it more desirable to people who can afford it. If people are willing to pay, why not max out the profit potential? What this means is that the average newly-built home is now pushing $650,0004 despite the fact that most San Diegans can barely afford half of that. If people can’t afford these homes, then who is buying them? It is either higher income individuals within San Diego County, possibly investors (foreign or otherwise) or higher income individuals moving from out of the region. About 20% of San Diego County households (those making over $150K per year) can afford homes costing $650K.

HOAs and Mello Roos reduce affordability significantly

Most newly-built market-rate homes include Community Facilities Districts (Mello Roos)5 which are an assessment to the new homeowners to help offset infrastructure costs. In addition, many have Homeowner Associations (HOAs) which, in 2015, averaged $327 per month.6 For every $100 of HOA or Mello Roos per month, the amount a household can afford drops about $16,000. So, for the typical HOA fee in newly built developments, the amount the buyer can get approved for drops $52,000. Add Mello Roos fees which can be $200 to $400 a month, it reduces affordability even further.

Eventually, market rate homes become affordable, right?

If we think that building enough high end homes will eventually “filter down” to the lower income folks, that has not happened so far in San Diego. What has been happening over the past several decades in the San Diego region is that builders have built market rate (high-end) homes at a much higher rate than entry-level or low end homes. In the last complete cycle of the Regional Housing Needs Assessment (RHNA), our region produced 152% of the State-mandated goals in the “above moderate” income housing, while at the same time producing around 20% of our RHNA goals for “moderate” income, “low” and “very low” segments.7

The current RHNA housing element cycle is, once again, producing tons of market rate, “above moderate” income housing and only a fraction of what is needed in the moderate or lower (about 14% of the goals). That is not surprising, as noted above, developers simply cannot build homes that are affordable to the median income household much less the lower income households—not without subsidies or grants or special financing.

As a result of this glut in higher end housing, we now have saturation of higher end housing, while at the same time we are in a massive deficit of lower end housing (about 14% of where we need to be according to the most recent RHNA progress report). And sales and construction is showing this slowness.

We’ve been seeing this in San Diego for some time: Harmony Grove Village, a large development that was fully approved for 742 homes almost a decade ago has, to this date, only built about 300 units and has had to offer promotions to attract more sales. These units should all have been built out by now. There are areas all over the County that show this same lack of construction, despite approved project entitlements, approved tentative maps and a high demand for housing. They have already surmounted their regulatory hurdles and there should be no obstacle to build the houses they were approved for. As the market continues to soften8 for the high end housing (interest rates going up, economy slowing), investors stop investing in projects because a higher internal rate of return is not guaranteed and housing prices will likely stop going up. The development industry depends on high prices to sell investors on projects. When prices go down, they slow production, thus constraining supply; costs rise again.

Increasing the supply of market rate housing does not guarantee that prices will go down. In fact, there is very little research on this topic and it is all over the place. As one example, the city of Vancouver, Canada, has built housing at a rate that exceeded their population growth consistently from 2001 to 2016, by 19%9. There is, in fact, a surplus of housing. And yet they’ve seen some of the highest price growth during that same period.10

The Federal Reserve also did a review of literature back in 2018 and were unable to find any research that showed that market rate housing would increase the affordability of housing overall. They had to create a (decidedly imperfect) model simulation to try to answer the question. They concluded that a 5% increase in supply in the most expensive neighborhoods would only reduce rents in those neighborhoods by less than 0.5%.11 So, we take this as a given that simply building more market rate housing will lower prices overall, based on flimsy evidence.

The housing market is complex and multi-layered

In essence, the housing market is composed of different submarkets, product types and customer classes, all of which have different targets, levels of demand and price sensitivity. The higher-end housing (whether luxury condos or McMansions in the ‘burbs) caters to a specific clientele and this is precisely what the building industry is producing en masse. The lower end, entry level housing is produced by affordable housing developers, typically non-profits that put together complex financing packages using public and private funding to build below-market-rate housing.

For-profit developers can no longer make this type of housing so the non-profits have stepped in. And still, simply building a ton of housing in one segment does not address affordability in the other segment because there is little cross-interaction (particularly from the lower to the higher segments). While the top tiers may see some softening (houses staying on the market longer with slower price growth) due to all this saturation, the lower tiers (entry level, sub-$500K housing) continues to suffer from extreme tightness because there are more households seeking housing in that price range than there is supply. Building exclusively high end housing will not address that because those folks simply cannot afford the higher end housing. So the low end supply is constrained and there is greater price inflation there than in the upper end.

Affordable housing is lacking nationwide too.

This is true in San Diego, but it is also true nationwide. The Joint Center for Housing Studies at Harvard University issued a report ( the State of the Nation’s Housing 2018), and it showed that 2.5 million apartments renting for less than $800 per month have been demolished, upgraded or converted into other uses since 1990. And between 2010 and 2017, prices in poor neighborhoods have risen 50% faster than prices in rich neighborhoods.

That is because the lack of construction of housing in the lower, entry-level tiers of the market.12 Further complicating this fact, is that, despite a growth in low income households (6 million total since 1988), housing assistance has stayed flat for several decades and recent changes to the tax code have reduced the value of Low Income Housing Tax Credits for businesses, resulting in a potential loss of 235,000 affordable units. We’re doing less to help lower income households afford housing even as those households are growing at a fast rate.

What this means, is that the average family and the lower income family in San Diego will continue to be housing burdened even as higher end homes and condos might sit on the market longer with prices flattening out. And, even more troubling, developers will likely slow building until the market moves in a direction that investors will want to exploit. Things that could likely help:

- increasing wages,

- attracting higher paying jobs to our region,

- limiting non-owner-occupied investment/vacation rentals,

- providing more low income housing assistance,

- providing more local, state and federal public funding for housing programs targeted at lower income households,

- All of the above.

We need to do more. Since private industry cannot deliver the type of housing that is needed to meet the needs of moderate and lower income households, we need to start thinking about what other levers can be pulled to make the housing market more equitable. We can’t rely on market rate housing alone.

Links and documents

- OC Register (1/17/2019), Southern California builders are cutting prices to move glut of unsold homes

- Pew Research (2018), For Most US Workers, Real Wages Have Barely Budged

- CA Department of Housing and Community Development, 2018 State Income Limits

- KPBS (Oct. 23, 2018) Home Prices Rise Year-Over-Year In San Diego County; Sales Drop

- iNewSource (2018) How much Mello Roos do you pay?

- Trulia (2017) Attack of the Killer HOA Fees

- SANDAG 2012, 4th Element Housing Cycle, Regional Housing Needs Assessment

- LA Times (12/27/2018) Southern California home sales drop 12% in November as price gains slow

- The Globe and Mail, Academic Takes on Vancouver’s Housing Supply Myth

- Conor Daugherty, NY Times, (6/2/2018), In Vancouver, a Housing Frenzy That Even Owners Want to End

- Finance and Economics Discussion Series Divisions of Research & Statistics and Monetary Affairs, Federal Reserve Board, Washington, D.C. (2018), Can More Housing Supply Solve the Affordability Crisis? Evidence from a Neighborhood Choice Model

- Joint Center for Housing Studies at Harvard University (2018), the State of the Nation’s Housing 2018