Barrio Logan Chicano Park (District 1). Photo courtesy of Flickr User: Paul Wasneski

This is part 2 of an ongoing series about the 2020 County Board of Supervisors race focusing on their land use and housing stances exclusively. Click here to start at the beginning.

What does this have to do with housing and land use?

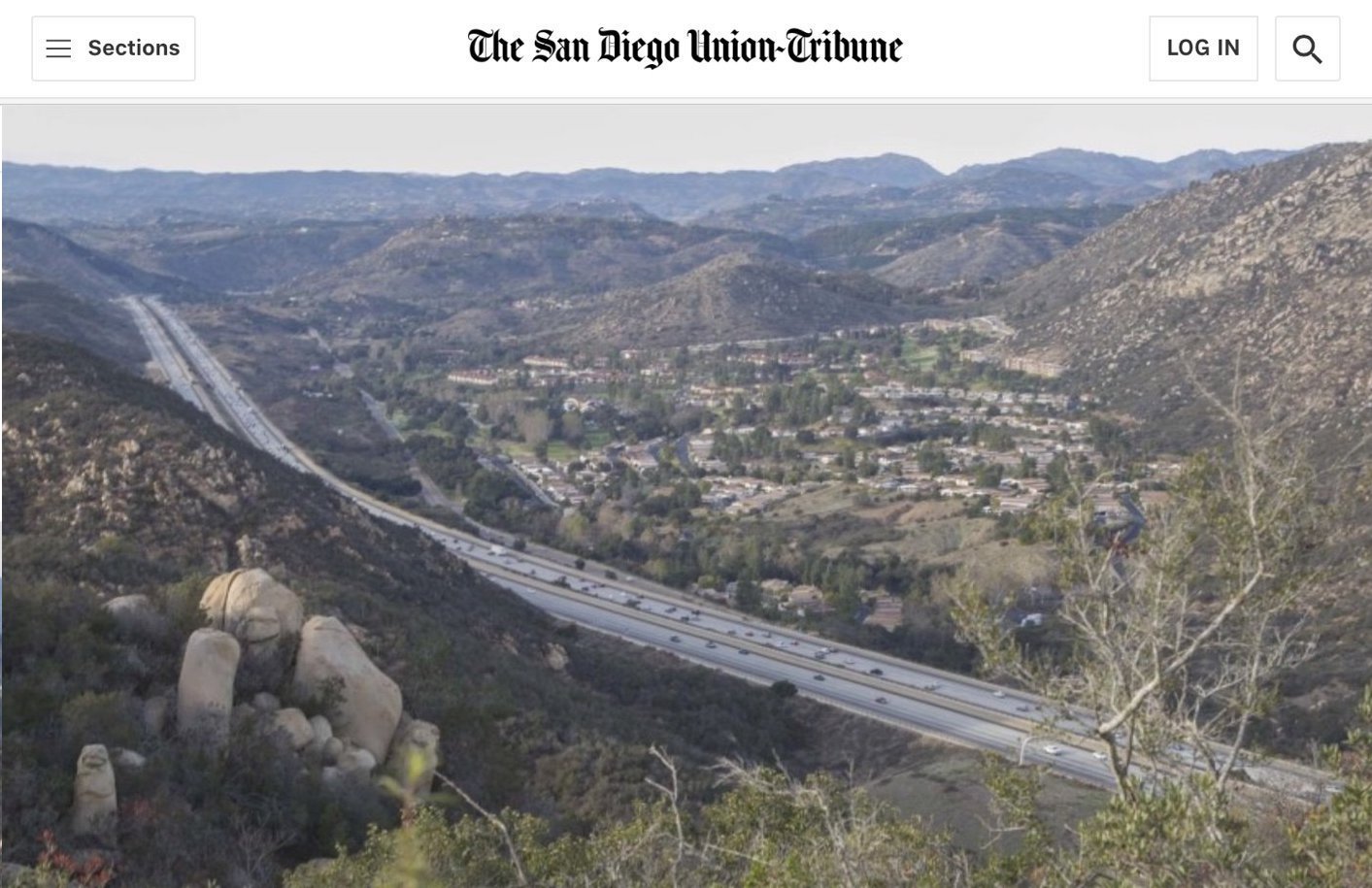

Well, the County Board of Supervisors wield ultimate authority in land use and housing decisions, but their purview is limited to the unincorporated areas of the County, which encompasses all the land outside of city jurisdictions. The unincorporated County is actually the second largest jurisdiction, by population, after the City of San Diego, and the largest by far in geographic area as shown below. It is composed of 26 distinct community planning areas and upwards of 100 smaller towns and villages. The unincorporated County is mostly rural and rural residential in nature with most of the County’s open space and agriculture.

While all five Supervisors preside over land use decisions that affect the unincorporated County, only 2 Supervisor Districts actually have significant areas of unincorporated County within their boundaries: District 2 and District 5 (currently held by Jacob and Desmond). Those two supervisors have the most to gain or lose in their land use decisions because they have a substantial voter base in the unincorporated County. Conversely, the other three supervisors’ constituents are located almost exclusively in cities who wield their own land use authority that the Supervisor has no jurisdiction over, so they don’t have as much political stake; their constituents aren’t as concerned about what happens in the unincorporated County. So, for those of us interested in smart planning and land use (as well as those living in the unincorporated area), the composition of the board is extremely important because they decide on the types of projects that get approved in the far-flung parts of our County, where most of our biodiversity, agriculture and and open spaces are located.

The County General Plan

The last Board approved a General Plan1 in 2011 that was forward thinking at the time. After 13 years of holding public workshops and hearings and spending upwards of $18 million in studies, consultants and staff time, the County approved a plan for land use and housing that adhered to smart planning and sustainability principles and shifted planned housing density closer to the western part of the County, near jobs and infrastructure, and away from the highest risk fire areas. This was a consensus-based plan that reflected the needs and vision of the local communities, the requirements mandated by state law as well as input from non-profits, environmentalists, housing advocates, real estate groups and the building industry. As far as plans go, it reflects the best thinking we have on urban planning and land use, though it presents numerous compromises between the many stakeholders involved. And, in fact, the General Plan accommodated more density than the state or SANDAG even required – approximately 68,000 parcels with by-right denser development potential.

Overall, the County General Plan dovetails with and is consistent with the overall regional strategy2 to meet our housing goals while limiting sprawl in the rural areas of the County and increasing density in the transit-oriented urbanized areas of our region. The County’s plan and the various cities plans work in tandem to maximize housing in the right places. This has the effect of reducing traffic congestion and helps meet the state’s climate change mandates by reducing pollution and greenhouse gases by locating more housing near jobs as well as encouraging transit usage. Since transportation is the number one driver of greenhouse gas emissions in California, reducing the distance between homes and jobs is crucial to meeting the state’s climate change requirements. The County’s plan, in essence, is a crucial component to the strategy of creating more density in urban areas, lowering traffic congestion, greenhouse gases and limiting sprawl.

General Plan Amendments on the line

Shortly after the General Plan was approved in 2011, hundreds of landowners, speculators and developers, with the encouragement of some of the supervisors at the time, proceeded to undermine the plan through various loopholes and a long pipeline of General Plan Amendments. GPA projects – as they are known by the wonkier types – are controversial because they request exemptions to the General Plan zoning and land use policies which only require a vote of 3 out of 5 supervisors to approve. State law therefore limits GPAs to no more than four per year for the very reason that they undermine the General Plan of a jurisdiction by creating loopholes or exemptions to the agreed upon roadmap for growth. Just last year, the Board voted to allow bundling multiple GPAs into one approval to sidestep the limitation of 4 per year, a fact exposed by Grow the San Diego Way and became an issue in the 2018 midterm elections. Last year they approved 5 GPAs3 and three more were stopped by the Sierra Club’s Climate Action Plan lawsuit4. Interestingly, one of the approved GPAs, Lake Jennings Marketplace, actually converted 160 residential housing units into commercial, despite the pleas for more housing in the County. The developer argued it would be hard to market apartments so close to the 8 freeway.

GPA developers typically target areas that the General Plan has specifically put off limits due to lack of fire safety, missing infrastructure, open space conservation, wildlife corridors, community preservation and the need to limit greenhouse gas emissions – all things that protect the public good. By approving too many GPAs, the Supervisors create a perverse incentive for speculators to hone in on land zoned for low-density housing, and hope that with enough lobbying they could get three out of five votes on the BOS to grant them much higher density, and thus extraordinary returns, on low cost assets. The fact Bill Horn, representing District 5, home to most sprawl project proposals, voted against the General Plan, opened the door for massive speculation.

Most of these large projects are funded by large institutional investors based outside of San Diego – as far away as a Japan (Newland Sierra, a joint venture with Sekisui House5), Minnesota (Lilac Hills, with major funding by Merced Capital) and Colorado (Harmony Grove Village South, funded by billionaire philanthropist, Marcel Arsenault of Real Capital Solutions), to name a few. These investors target rural or agricultural land that is off limits to development (and thus has a lower development value). They purchase the “undervalued land” with the objective of lobbying the local politicians to change the zoning to favor their projects, thus increasing the value of their land manyfold with a simple 3-out-of-5 vote majority. Needless to say, these investors and the developers they partner with spend millions and millions of dollars on local campaigns, PR and lobbyists in order to ensure a good return on their investment. And largely it has worked due to a friendly board of supervisors

In Part 3, we will look at the current Board of Supervisors and see where it stands when it comes to land use and housing and where it might be headed. Continue to Part 3: The political environment today

Photo courtesy of Flickr User: Paul Wasneski, used with Creative Commons license

Links and documents

- A General Plan is a plan for housing, zoning and land use that is mandated by the State for every jurisdiction. It allocates the various land use designations (residential, commercial, rural, agricultural) to specific locations to meet the State’s housing requirements.

- From SANDAG’s Regional Transit Oriented Development Strategy: “The overarching strategy set forth in the Regional Plan is to: (a) focus housing and job growth in the urbanized areas where there is existing and planned infrastructure b) protect sensitive habitat and open space (c) invest in a network that gives residents and workers transportation options that reduce greenhouse gas emissions (d) promote equity for all (e) implement the plan through incentives and collaboration

- Lake Jennings Marketplace, a bundled approval that included Harmony Grove Village South, Valiano and Otay 250 and Newland Sierra

- For more background on the Sierra Club lawsuit and its implications, click here

- North American Sekisui House, Japan’s largest homebuilder