The framework of a home remains standing after the Lilac Fires engulfs a Fallbrook community. / Photo by Adriana Heldiz / Voice of San Diego.

Grow the San Diego Way is a think-tank and advocacy that promotes principles of smart land use and planning for a more equitable, livable and sustainable San Diego County.

Our latest Op Ed in Voice of San Diego responds to the ongoing building industry narrative that downplays the risk of sprawl development in high risk wildfire corridors. Due to space constraints, some key points had to be edited out. Below is the unabridged version. Please make sure to visit or subscribe to Voice of San Diego to thank them for giving organizations like ours the opportunity to voice our perspective.

Advocates for car-centric, sprawl projects in fire country ignore basic tenets of fire science when pushing for dangerous, unsustainable projects.

In the past 20 months, California has seen nine of the largest fires in state history and lost more than 20,000 homes to wildfires. A million homes face wildfire risk in California, 88,000 in San Diego alone. Scientists are telling us that wildfires will increase in frequency and severity over the coming decades and are telling us that we need to shift our building pattern from sprawl in rural areas to more urbanized infill areas.

With that backdrop, well-meaning, but tone-deaf advocates for car-centric sprawl attempt to blindly dismiss concerns about fire risk in a recent op-ed at Voice of San Diego. The op-ed touts how safe construction standards will protect the new project and was penned by Ginger Hitzke, an affordable housing developer (full disclosure, she’s a friend of Grow the San Diego Way, though we disagree on this rather important matter) and Richard Montague, the CEO of developer-side fire consulting firm, Firewise 2000, consultants for Lilac Hills Ranch, Safari Highlands and Valiano, among other sprawl developments, so we can see where his loyalties lie. The op-ed mirrors quite closely the Building Industry Association’s ongoing public affairs push on downplaying fire risk (which is to say, we shouldn’t worry about it).

Coming as it does, only a few weeks before the June 26 Board of Supervisor’s hearing on a controversial General Plan Amendment project in a major wildfire corridor, Otay Ranch Village 14, we thought it would be important to set the record straight.

The consensus-based, smart-growth-oriented general plan specifically avoids development in high fire risk areas

The County’s latest general plan took over 13 years and $18 million to develop. It involved hundreds of workshops involving multiple stakeholders ranging from communities to environmental groups to the building industry as well as our public safety officials. One of main guiding principles of the County’s general plan (Guiding Principle 5) specifically outlines its philosophy on wildfire risk and land use and explains why much of the land in the riskier areas of the County was purposefully left as lower density:

New development should be located and designed to protect life and property from these and similar hazards. In high risk areas, development should be prohibited or restricted in type and/or density. In other areas, structures, properties, infrastructure, and other improvements should be designed to mitigate potential risks from these hazards.1

These and other principles helped concentrate density in smart growth areas and villages, closer to the west of the County (and nearer to jobs). It is important to note that the general plan was a consensus driven plan that was a result of many years of planning and compromise between a great many stakeholders at great cost to the taxpayer. General plan amendments (GPAs) therefore need to adhere to the principles of the general plan otherwise we risk disassembling the general plan based solely on the profit motive of privately held corporations in a rather undemocratic fashion. Arguably, one of the most important principles in the general plan revolves around public safety and wildfire risk is among the biggest.

“But there are High Fire Zones everywhere, so we have no choice but to build in them.”

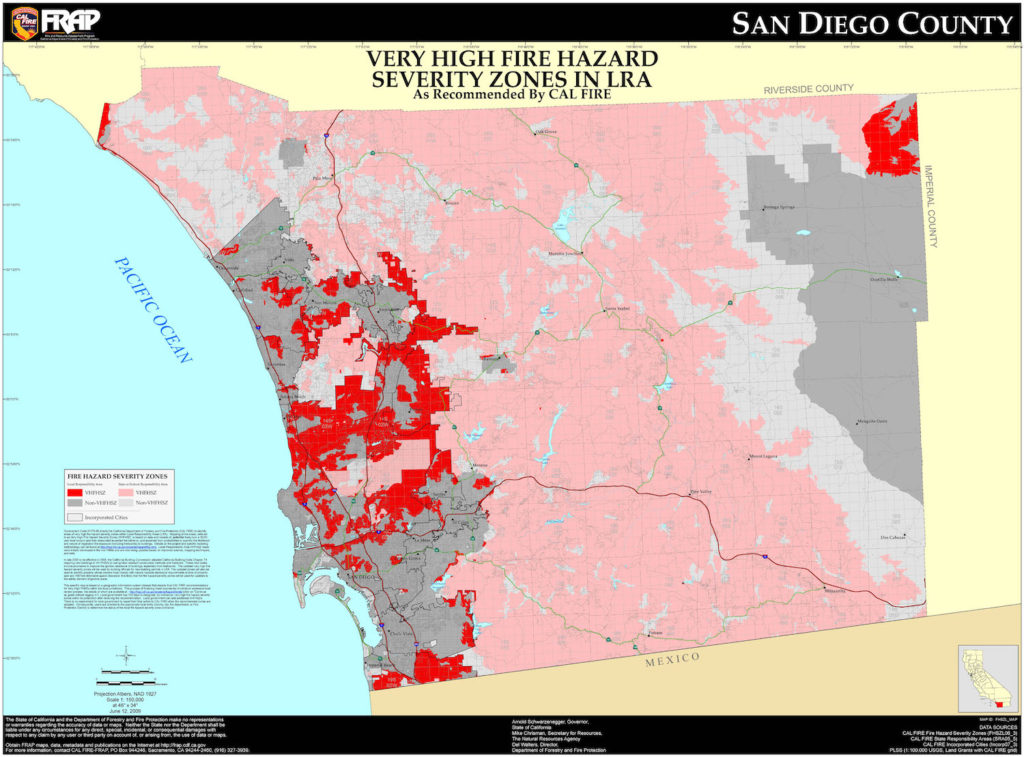

One argument the authors (and the BIA) make for high risk sprawl projects is that the entire San Diego region is in a Very High Fire Severity Zone and therefore, to limit construction in these zones would essentially kill construction everywhere. Of course, this is a strawman argument because no one is suggesting that, and furthermore, it is incorrect.

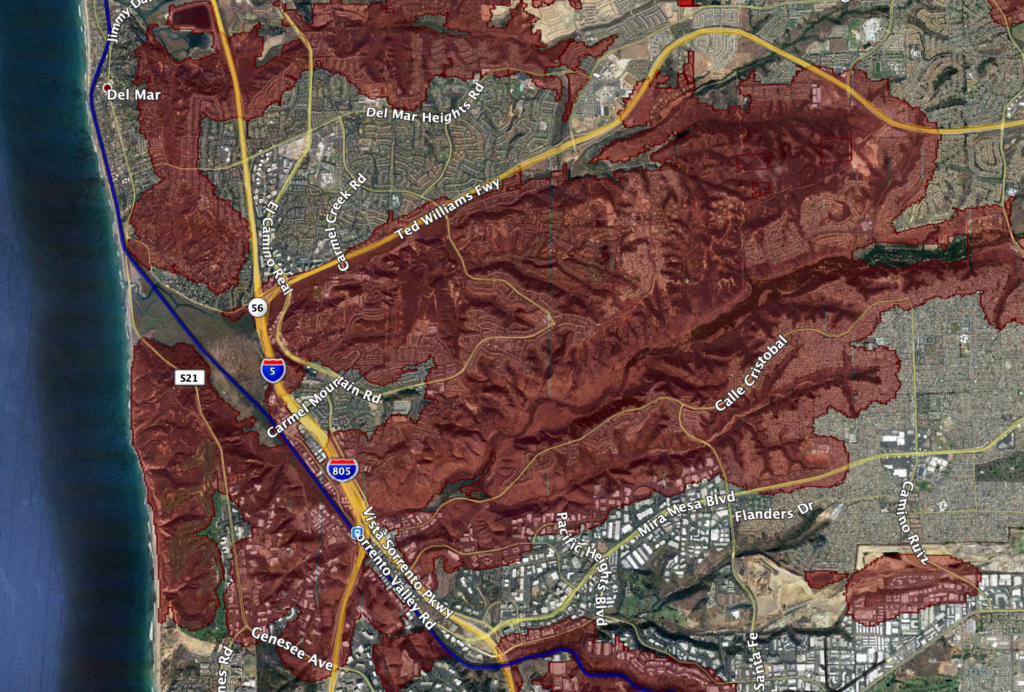

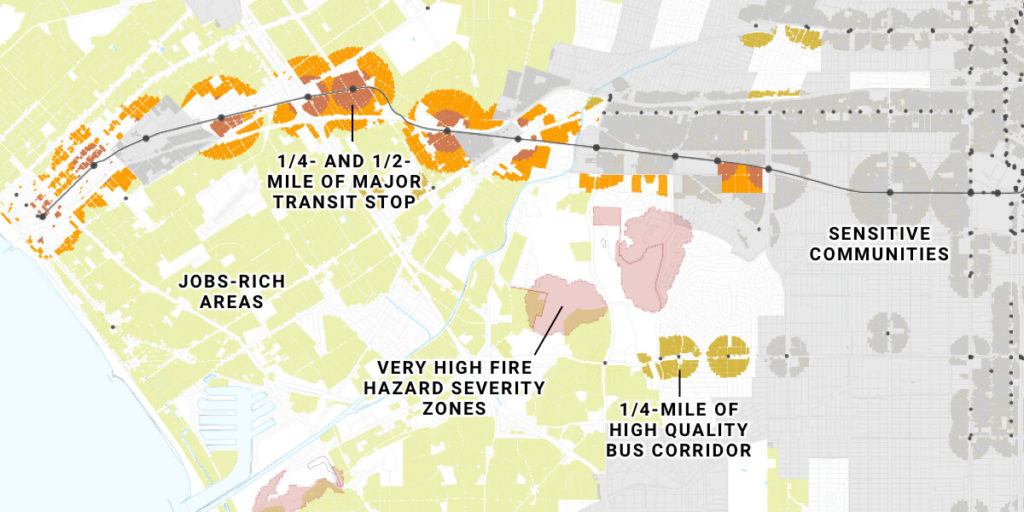

Cal Fire’s scientifically-derived Fire Hazard Severity Zones overlays are based on available fuel load, topography and a high likelihood that a fire could start and spread quickly in a particular area. If you look at the map of San Diego County you will see that, indeed, much of it is covered in very high Fire hazard severity zones (VHFHS). The largest, contiguous swaths of VHFSZ are in the undeveloped areas of East and North unincorporated San Diego County. However, digging a little deeper into the data, we can see that in the urban areas of San Diego, the “very high” fire hazard zones typically are areas adjacent to canyons, parks or open space preserves (like Torrey Pines, Carmel Mountain or Miramar).

These are clearly very different areas. The latter is more defensible because it has urban development surrounding it, which limits fuel for a fire to spread, more evacuation routes and better fire suppression potential. The former has over a million acres of contiguous brush and open space creating the conditions for wildfires like the Cedar Fire in October 2003, that burned at the rate of 46 football fields per minute for a total of a quarter of a million acres, destroying 2800 structures and killing 12 people. These are areas that the county’s general plan has specifically limited development in due to the very high fire risk. Conflating the fire risk from urban and rural areas is inaccurate and more subterfuge meant to weaken the argument against building developments in the backcountry.

The following interactive map lets you see if you’re in a Very High Fire Severity Zone. There is also a layer for historical fire perimeters, if you’re curious.

Http iframes are not shown in https pages in many major browsers. Please read this post for details.What does fire science say about the difference between rural and urban fire risk?

Established science shows that the majority of property damage, fatalities and destruction from wildfire in California is located in less dense, rural areas. A recent study focused on all major areas of California including San Diego County, and their findings were:

“For all study areas, most structure loss occurred in areas with low housing density (from 0.08 to 2.01 units/ha), and expansion of rural residential land use increased structure loss probability in the future.”2

In essence, they are saying that land use planning should avoid low density, rural areas because these are the areas with a high probability of ignition and a high likelihood of structure loss increasing into the near future.

This is not controversial; it is common knowledge

A recent report by Governor Newsom’s wildfire strike force wisely recommends that the State:

“begin to deprioritize new development in areas of the most extreme fire risk. In turn, more urban and lower-risk regions in the state must prioritize increasing infill development and overall housing production.” 3

That’s because, according to the Fourth Climate Assessment, frequency of severe wildfires will increase 50% and the average area burned statewide will increase by an estimated 77 percent by 2100.

Outgoing CalFire Director, Ken Pimlott, told the Associated Press last fall, “we must consider prohibiting construction in particularly vulnerable areas.”

Even Scott Weiner’s recent controversial housing bill, SB50, created exemptions to increased density in very high fire severity zones.

That is because our decision-makers recognize that encouraging infill and urban density is more sustainable, reduces VMTs and greenhouse gases and importantly, is much less likely to be destroyed by the increasingly frequent wildfires the state will be facing in the coming decades.

Better construction standards and shelter-in-place are not viable solutions

Pro-sprawl activists claim that the County will protect these far flung, sprawl developments through hardened construction standards, shelter-in-place policies and orderly, staged evacuations. None of this is backed by science and, in fact, puts people in harm’s way.

A great many homes built to the highest fire standards burned down during the last few wildfire seasons.

Existing construction standards for homes in high fire risk areas are already very stringent and yes, they do improve the chances that a house will survive a fire. Still, the risk is still there and the odds of survival are still not much better than winning a coin toss.

In the Camp Fire, which destroyed 18,000 homes and decimated the town of Paradise, it turns out that about half of the homes built after 2008, using the latest wildfire resistant construction standards touted by the industry, did not survive. Of course, half did survive which attests to the importance of increasing your odds of survival if you have fire hardened construction standards, but, certainly these odds are hardly encouraging.

In the Tubbs fire (October 2017), 86% of the homes built after 2008, with the highest wildfire construction standards, were destroyed anyways. Non-combustible siding, roofing, interior sprinklers, enclosed eaves were no match for softball sized embers slamming into homes at 60 mph. Shelter-in-place should only be used as a last resort, not as the primary means to protect a community.

The Thomas Fire (December 2017) also showed that the improved fire construction standards were not enough in the kinds of wind-driven fires that are becoming more commonplace. More than 90% of the structures destroyed had fire-resistant construction.

So, even though the risk is reduced with newer construction standards, the clustering of housing typical in sprawl development projects increase the likelihood that those houses that do catch fire will become, themselves, fuel for the other houses due to their proximity.

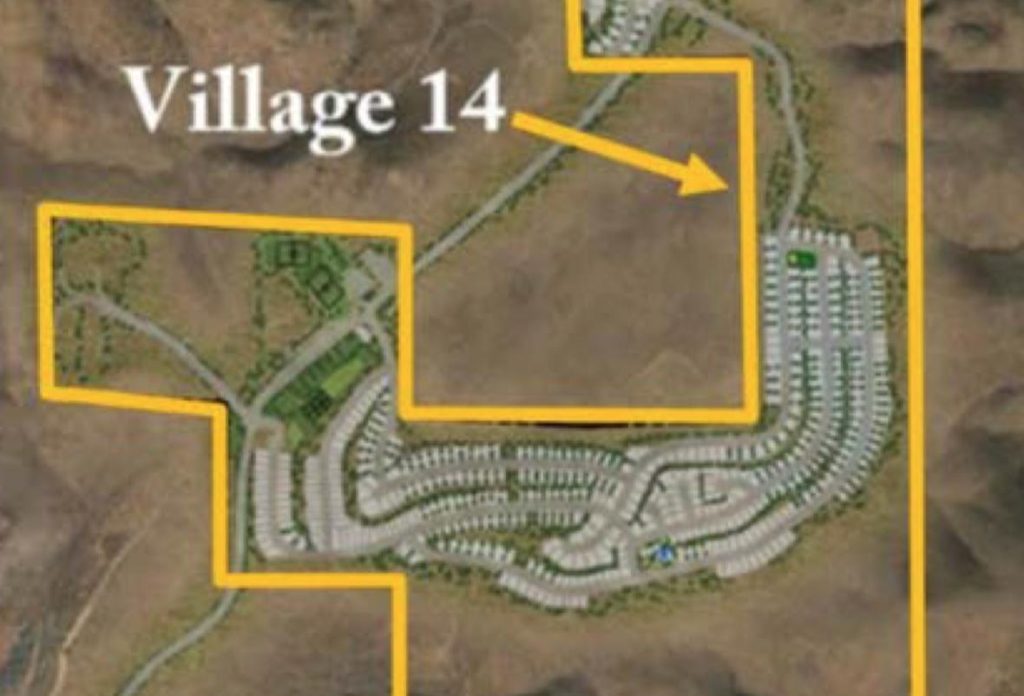

Here’s what the next sprawl project in the pipeline (Otay Ranch Village 14) looks like:

Houses that are closer together are more likely to spread fire than those far apart. In fact, some studies show that houses contain more flammable material inside them per yard than in a forest.

"There is actually more flammable material in a house per square yard than in a forest," said Michael Ghil, UCLA distinguished professor of climate dynamics and geosciences and co-author of the research, which will be published in the Sept. 4 print edition of Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.4

It’s the evacuation, stupid

This focus on fire construction standards is simply a way for the proponents of these massive projects to sidestep the real issue and that is evacuation capacity. Of course, we should make every effort to make structures more fire-resistant. That’s a no brainer. Regardless, whether or not homes are fire-hardened, the safest option is to leave early, given the poor performance of this type of construction in recent fires. Yes, better construction standards may increase your odds of survival from 18% to 51%, but that is still akin to flipping a coin. Will residents in wildfire zones take that chance to shelter-in-place? Indeed not. Most will flee. And during evacuation is where most fatalities occur. 5

Lessons from Australia on Stay and Defend or Leave Early

Before 2009, Australia’s official policy for residents in wildfire risk areas was known as “Stay and Defend or Leave Early.” Research had shown that it was possible to survive a a fast-moving wildfire front in certain scenarios by hunkering down and then immediately extinguishing smoldering embers after the front passed through. However, in 2009, after what is now known as Black Saturday, a fire event more severe than what Australians were accustomed to overwhelmed communities and 173 people died, most of whom were in or around their homes. Unlike other bushfires, it was driven by 60 mile-per-hour winds which made defending structure much more difficult and helped the fire spread at an alarming rate. This is what makes our own Santa-Ana fires so much more dangerous than traditional wildfires.

Santa Ana-driven fires are much more destructive and faster moving

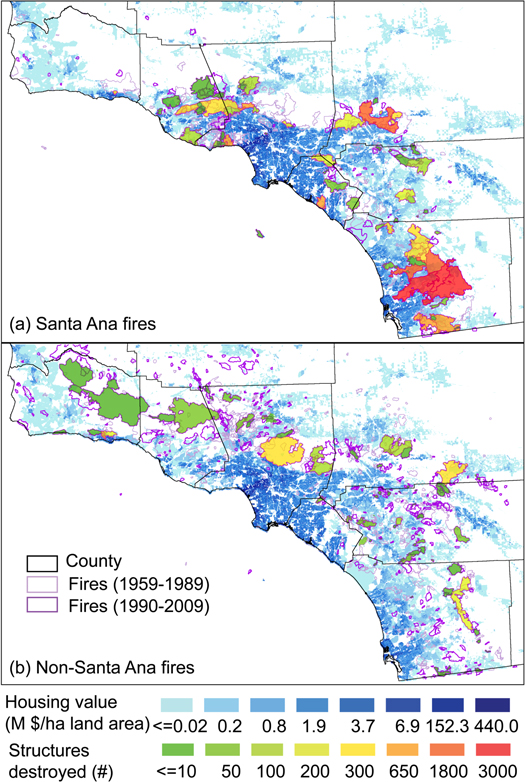

The majority of fires that have caused structure damage in our region are Santa Ana-driven fires. According to recent studies of wildfire patterns in California, Santa Ana-driven fires cause an 8-fold increase in impacts compared to non Santa-Ana driven fires largely because a) they are more likely to occur in more populated areas, blowing westerly towards urban areas and b) because, instead of a steady moving fire front, you have a wind-driven fire that can blow burning embers at 60 to 100 miles-per-hour, crossing freeways (as it did during the Cedar Fire) and pelting homes with softball sized fireballs. From a comprehensive analysis of wildfires across California by fire scientists from UCLA, UC Irvine and UC Davis:

We found that Santa Ana fires placed considerably more structures and human lives at risk (with more than 7 fold higher impacts than non-Santa Ana fires), whereas suppression expenditures were slightly lower for this fire type.6

Santa Ana fires will be getting significantly worse and more frequent

Numerous studies have concluded that climate change will be creating significantly more dangerous fire conditions, especially for those living in the rural, high risk fire areas.

[the analysis] predicted more intense Santa Ana events, which are expected to increase fire size, mostly by reducing relative humidity and secondly by increasing wind speed . The overall area burned by Santa Ana fires increased 64% on average.7

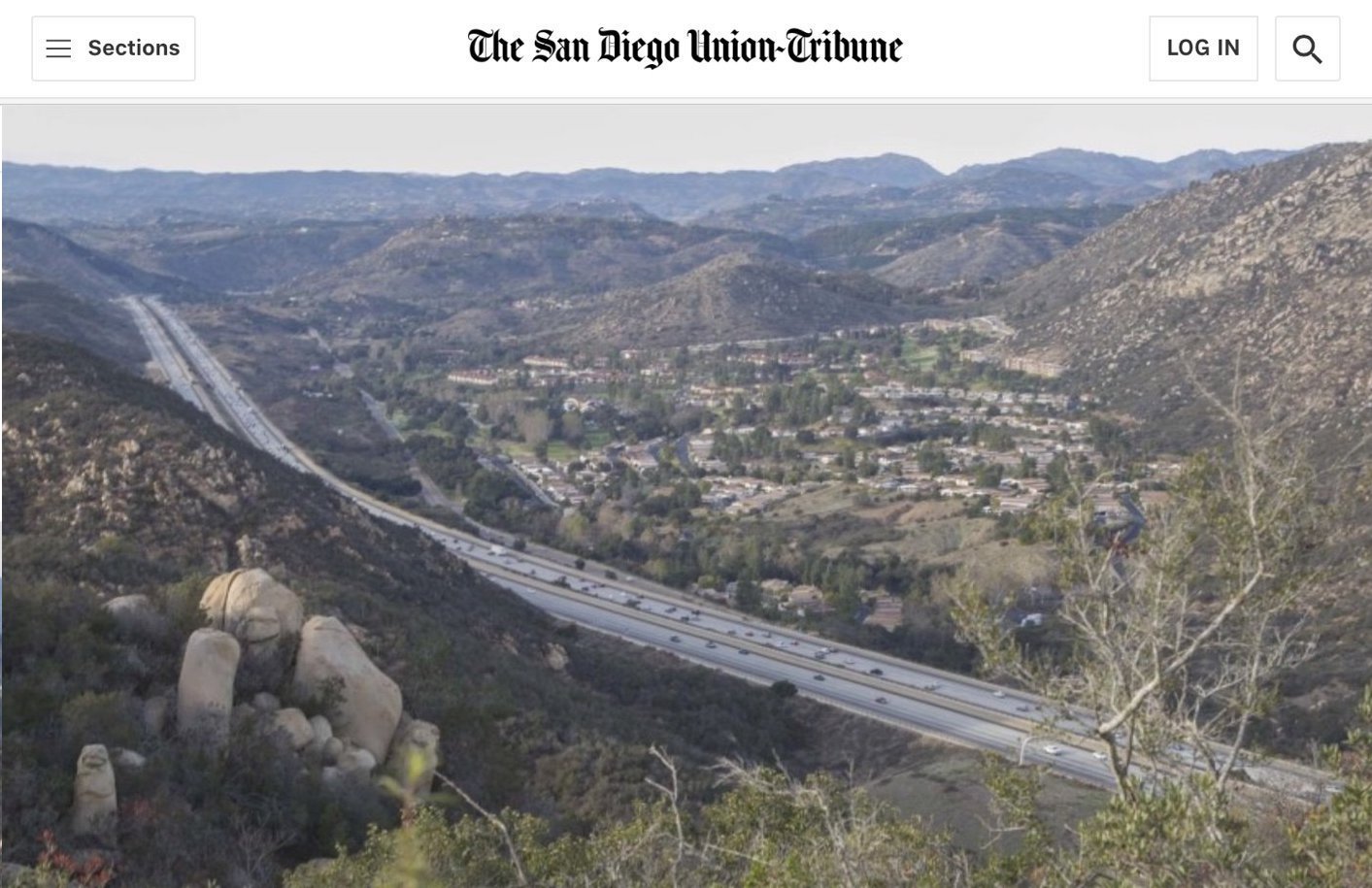

And unincorporated San Diego County has serious evacuation issues

The areas where most of these general-plan-amending, sprawl projects are being proposed are in known wildfire corridors that have a regular history of fire activity and limited two lane rural roads that serve as evacuation routes. It is one of the reasons those areas have been zoned for lower density in the first place.

During Coco’s Fire in May 2014, thousands of cars were at a standstill for close to two hours while wildfire burned less than a mile uphill from residents of San Elijo Hills. A last-minute change of wind direction is what prevented a potential catastrophe.

A recent analysis by the Associated Press evaluated California communities and evacuation routes and found numerous areas in San Diego County that were considered in the top 1% of worst communities in the state when it comes to population-to-evacuation-route ratios including Jamul, Ramona and Scripps Ranch.

Below is an interactive map that allows you to see how your area fares when it comes to population-to-evacuation ratio.

The area around Jamul (adjacent to the next project on the Board of Supervisor’s agenda, Otay Ranch Village 14 ) is one of the worst areas for its lack of evacuation throughput and the site of multiple large fires including the 90,000 acre Harris fire and the 174,000 acre Laguna fire.

What does the science say about “staged evacuations?”

The head of the County Fire Authority, Chief Mecham, has given his blessing to sprawl projects in high risk areas (including waivers to fire code requirements like secondary egress) by saying that the errors of the past will be corrected by a more “surgical” evacuation system (otherwise known as “staged evacuations) whereby people will be evacuated by neighborhood in order to avoid gridlock rather than issue an overall (simultaneous) evacuation order.

A study in the Journal of Operational Research looked at the effectiveness of staged evacuations by comparing multiple strategies in different road network types. It found that staged evacuations are no better than simultaneous evacuations in “ring or real road” networks found in rural areas. So, in essence, our public safety personnel are offering strategies that science shows us are not effective.

There is no evacuation strategy that can be considered as the best strategy across different road network structures, and the performance of the strategies depends on both road network structure and population density; There is no clear advantage to use the staged evacuation strategy when the underlying transportation is a ring road network even if the population density is high. 8

The mayor of Paradise, who also happened to be a traffic engineer, meticulously planned for fire evacuations including community-wide drills and a staged evacuation system. Needless to say, the system failed spectacularly, and the entire town was destroyed. San Diego County has not implemented anything resembling this level of evacuation planning in the unincorporated communities. In essence, those charged with our safety are using anecdote and ignoring science to dismiss fire safety concerns.

The County and sprawl developers do not conduct thorough evacuation analyses

As the County contemplates approving General Plan Amendments projects in the rural areas of the County such as Lilac Hills and Otay 14, they have ignored the realities of evacuating rural communities. One would think that to ensure the safety of a project and the surrounding community, the County would look at the total volume of vehicles and the capacity of the existing roads during an evacuation scenario to ensure that the entire area can be evacuated efficiently. Incredibly, that analysis is not conducted.

When a project comes to the County seeking a general plan amendment in very high risk fire hazard zones, they are required by the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) to develop a fire protection plan (FPP) and occasionally, a wildland fire evacuation plan (WFEP). Both plans focus on the new development itself and how it would fare during a wildfire, and completely ignores the surrounding area. A community-wide evacuation plan is not required by County or State law that would analyze the impact of existing residents evacuating or existing “ambient” traffic that would be in the area during a wildfire event.

In fact, the aforementioned project, Otay Ranch Village 14, provides an evacuation plan that ignores the more than 6,000 residents of Jamul that would be evacuating along the same road as well as the existing thousands of vehicles (ambient traffic) that are routinely on Proctor Valley Road on any given day. Combined with the development’s evacuation traffic, volume would overwhelm the road’s ability to get people out in a timely manner.

In summary:

There are numerous car-centric, sprawl projects being proposed through General Plan Amendments in the rural, unincorporated County including Lilac Hills and Otay Ranch Village 14 / Planning areas 16/19. They are in known fire corridors and adjacent to hundreds of thousands of acres of open space and they have been identified as having extremely poor evacuation throughput. It is incumbent upon our decision-makers to decide whether or not we should be placing more people in harm’s way by encouraging more high fire risk sprawl projects in the rural areas of the County or if we should wisely continue to focus on infill and redevelopment areas where the risks are lower and the infrastructure is better.

JP Theberge is the Executive Director of Grow the San Diego Way whose mission is to provide research-based objective data on the housing affordability crisis in San Diego with the hopes of bringing citizens, planners, economists, builders and decision-makers together to help solve the problem in a way that best benefits all communities. He is also the President of Cultural Edge Consulting, Inc., a public opinion and market research company focused on cross-cultural targets.

Links and documents

- 2011 County of San Diego, General Plan

- Syphard AD, Bar Massada A, Butsic V, Keeley JE (2013) Land Use Planning and Wildfire: Development Policies Influence Future Probability of Housing Loss. PLoS ONE 8(8): e71708. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0071708

- (2019) State of California, Office of the Governor, Wildfires and Climate Change:California’s Energy Future, A Report from Governor Newsom’s Strike Force

- University of California - Los Angeles. (2007, August 30). Wildfires: Homes Fuel The Fires More Than Forests. ScienceDaily. Retrieved June 7, 2019 from www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2007/08/070828110719.htm https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2007/08/070828110719.htm

- K. Haynes et al, Australian bushfire fatalities 1900–2008: Exploring trends in relation to the ‘Prepare, stay and defend or leave early’ policy, Environmental science & policy 13 (2010).

- Yufang Jin et al Identification of two distinct fire regimes in Southern California: implications for economic impact and future change. Environmental Research Letters 10, 094005 (2015)

- Yufang Jin et al Identification of two distinct fire regimes in Southern California: implications for economic impact and future change. Environmental Research Letters 10, 094005 (2015)

- Chen, Xuwei & B Zhan, F. (2008). Agent-Based Modelling and Simulation of Urban Evacuation: Relative Effectiveness of Simultaneous and Staged Evacuation Strategies. Journal of the Operational Research Society. 59. 10.1057/palgrave.jors.2602321

Impressive rebuttal, with solid scientific analysis to form accurate counter-arguments to Op Ed published in Voice of San Diego, written by Ginger Hitzke and R. Monatgue, which applied fantasy planning about staged evacuations. This prompt rebuttal by Grow the San Diego Way will correct the record, which so far has been extremely distorted by building industry advocates for high density development rural areas identified as Very High Fire Hazard Severity Zones in LRA/SRA, identified by CalFire. It’s crucial to correct the record, using best available fire science data, traffic data and sound planning principles.

Good timing to introduce fresh new perspective before the June 26, 2019 public hearing at County of San Diego Board of Supervisors meeting (9 am), when Board considers Otay R;anch Village 14.