Our latest Op Ed in Voice of San Diego received a lot of attention, so much so that the Union Tribune saw fit to publish an editorial the very next day defending the latest firetrap development being proposed in the County. The editorial, like much of what is provided by industry-backed PR firms, is full of inconsistencies and inaccuracies.

The County’s general plan calls for increased housing in strategically-located areas around the county where there is the least amount of fire risk and nearer to denser villages with plenty of infrastructure. This careful plan took 13 years, involved hundreds of community and stakeholder meetings and cost $18 million dollars to put together. Unfortunately, that plan is being disassembled piecemeal by haphazard General Plan Amendments which disregard the risks that the plan was intended to mitigate.

The San Diego Union-Tribune’s editorial board recently put together a pro-firetrap sprawl editorial, mirroring closely the sprawl developer’s primary PR strategy: downplay catastrophic fire risk in one of the areas with the highest fire risk in the County.

Once again, they are touting the building industry line, “construction standards are better now, nothing to worry about.” The main premise is that Rancho Santa Fe did ok during the Witch fire with its more wildfire resistant standards so we shouldn’t worry about the backcountry sprawl projects that will use similar standards. The premise is flawed. Let’s take a look at their various arguments:

Rancho Santa Fe survived the Witch Fire due to improved construction standards, so sprawl projects will too.

This argument is quite misleading. The authors are conflating large lot, rural homes in one of the wealthiest communities in the country with sprawl developments where hundreds of houses are clustered closely together.

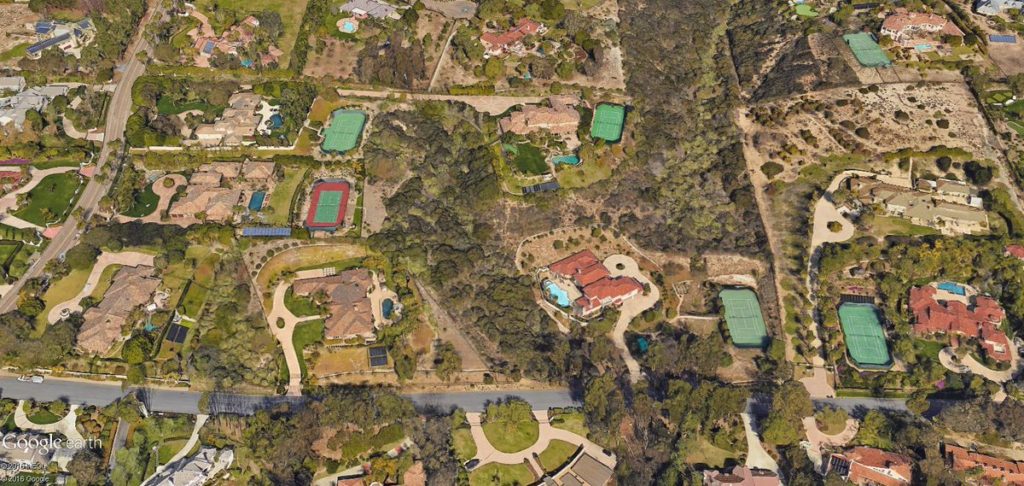

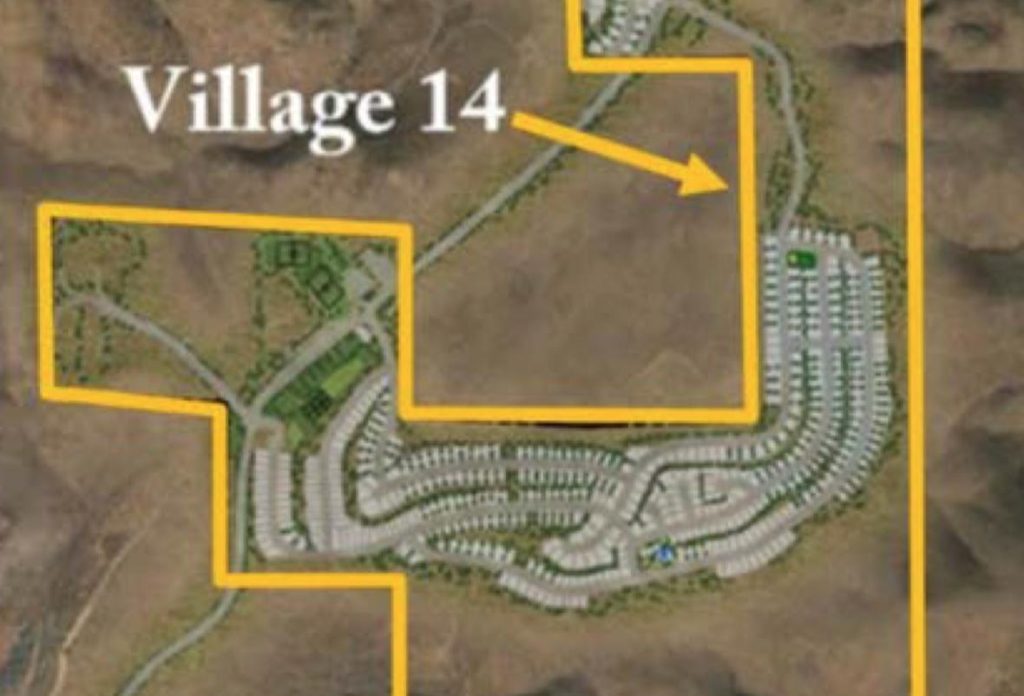

Rancho Santa Fe is nothing like the projects being proposed. These are large lots of two acres or more, with $5 million dollar houses complete with full-time landscaping staffs that maintain defensible space year round. Sprawl developments like The Otay Village 14 / Planning Area 16 project have houses closely spaced together and it is this proximity that creates conditions for fires to spread quickly as the houses themselves become fuel and spread quickly. Here’s a view of Rancho Santa Fe housing from a bird’s eye view:

Note how the houses are spread far apart and are mostly manicured and well maintained? Here’s what the next sprawl project in the pipeline (Otay Ranch Village 14) looks like:

Houses that are closer together are more likely to spread fire than those far apart. In fact, some studies show that houses contain more flammable material inside them per yard than in a forest.

"There is actually more flammable material in a house per square yard than in a forest," said Michael Ghil, UCLA distinguished professor of climate dynamics and geosciences and co-author of the research, which will be published in the Sept. 4 print edition of Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The study also recommends fire hardening for those who live in high risk fire area as those houses do not burn as quickly. We should encourage all those who live in the wildland urban interface to make their homes more resistant to fire. Nonetheless, swimming in shark-infested waters is also a lot safer if you wear puncture resistant gear, but it’s better to avoid swimming in that water altogether, if you can avoid it.

Rancho Santa Fe still had significant structure loss during the Witch Fire.

Aside from the obvious benefits of living amongst billionaires and millionaires, Rancho Santa Fe has one of the best fire districts in the County with more resources per household than the County Fire Authority. They have a full time staff that conducts yearly defensible space inspections on almost every house in the district. The County Fire Authority just recently announced they would expand their inspections which, once implemented will only hit a paltry 12% of the houses in the unincorporated County every year.

The Witch fire spared most of RSF mostly due to the heroic efforts of the RSF Fire District firefighters who dutifully protected the homes and due to some good fortune as well . And yes, while more recently-built homes using the more strict wildfire standards survived, it was more a result of good, defensive space practices and the army of firefighters posted in the area to protect the extremely valuable high-end homes. Still, 61 homes throughout the fire district did burn.

The latest wildland urban interface construction standards did not save hundreds of homes in the firestorms of 2017 and 2018.

According to an analysis of Cal Fire data from the Tubbs Fire defies that logic: A building code update added new fireproofing standards for homes in the wildland-urban interface in 2008. Yet, according to the Cal Fire inventory, 87% of the homes built after that year in the Tubbs Fire footprint were destroyed. (Should Development be Extinguished on California’s Fire Prone Hills?)

In the Thomas Fire, fire protection measures did little to protect housing that employed fire hardening measures. 90% of the houses destroyed or damaged had employed fire hardening measures: non-combustible roofing (90%), non-combustible siding (80%), multi paned windows (45%), enclosed eaves (43%) among other interventions.

In the Camp Fire, which destroyed 18,000 homes and decimated the town of Paradise, it turns out that almost half (179) of the homes built after 2008, using latest wildfire resistant construction standards did not survive. Of course, half did survive which attests to the importance of increasing your odds of survival if you have fire hardened construction standards, but certainly these odds are hardly encouraging.

The bigger issue is evacuation infrastructure

The most glaring lapse in the argument about whether or not we should be building in the riskiest of wildfire prone areas is the complete inattention to evacuation, which is where the greatest number of fatalities can occur. Regardless of how well-constructed a home is, as shown above, even the most hardened homes have a good chance of burning. As such, shelter-in-place is a worst case scenario and mass evacuation is inevitable. When a fire occurs, communities evacuate either by order or out of fear. Yet, this is where we place the least amount of due diligence and analysis.

A recent study by The Associated Press looked at all the areas in California listed as Very High Fire Severity zones by CalFire and then assessed the evacuation capacity of those areas by looking at the ratio of population per lane capacity. There were 23 areas (including Paradise) identified as being in the worst 1% in the state when it comes to population-to-evacuation ratios. Of those 23, three were in San Diego County and, one of the worst areas was precisely where a developer is proposing a large sprawl project. This very project, Otay Village 14 and Planning Areas 16/19 (Adara at Otay Ranch), is the one that the Union Tribune appears to be shilling for in their editorial as it is coming in front of the Board of Supervisors on June 26th. When architects plan for a building, fire code requires them to ensure there are sufficient exits and a maximum capacity to avoid entrapment during a fire. If you only have one exit that can safely accommodate 100 people, you cannot double or triple the number of people without increasing the exits. Unfortunately, our land use planning does not follow the same philosophy.

Below is an interactive map that allows you to see how your area fares when it comes to population-to-evacuation ratio.

The area around Jamul is one of the worst areas for its lack of evacuation throughput and the site of multiple large fires including the 90,000 acre Harris fire (2007) and the 174,000 acre Laguna fire.

The County does not require developers to analyze evacuation capacity beyond projects’ future residents.

When a project comes to the County seeking a general plan amendment in very high risk fire hazard zones, they are required by the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) to develop a fire protection plan (FPP) and occasionally, a wildland fire evacuation plan (WFEP). Both plans focus on the development itself and how it would fare during a wildfire. The evacuation plan, however, is not required by County or State law to analyze the impact that existing residents evacuating or existing “ambient” traffic that would be in the area during a wildfire event. In fact, the aforementioned project provides an evacuation plan that ignores both the 6,000+ residents of Jamul that would be evacuating along the same road and the existing thousands of vehicles that are routinely on Proctor Valley Road on any given day. In our op-ed, we reference how east coast cities model area-wide evacuations using statistical methods and GIS modeling. We would be well served to do the same before adding 2,400 more vehicles onto severely constrained evacuation routes. At the bare minimum, we should understand how areawide evacuation will be impacted by new projects in high risk areas.

The County is not alone in its lack of a cohesive evacuation strategy

Only 22% of the communities identified by the Associated Press as being the most at risk of fire around the state have a specific detailed evacuation plan that the public participates in. The Town of Paradise had zone-based detailed evacuation plans which had been effective in the past. The plan is mailed to every home in Paradise each year and the community actually conducted evacuation drills. San Diego County has improved its emergency response and evacuation protocols in recent years, but residents are blissfully unaware and not coordinated in any meaningful way to be prepared for evacuation. While, like anything else, you can’t always plan for all circumstances, at least some planning is better than none.

We absolutely should deprioritize developments in high risk fire corridors.

A recent report by Gov. Gavin Newsom’s wildfire strike force wisely recommends that the state “begin to deprioritize new development in areas of the most extreme fire risk. In turn, more urban and lower-risk regions in the state must prioritize increasing infill development and overall housing production.”

Outgoing CalFire Director Ken Pimlott told the Associated Press last fall, “we must consider prohibiting construction in particularly vulnerable areas.” Even Sen. Scott Weiner’s recent controversial housing bill, SB 50, created exemptions to increased density in ”very high” fire zones.

So, shifting our land use patterns to something more sustainable helps keep people from being put at risk, but it also reduces greenhouse gas emissions, reduces vehicle miles traveled and reduces our over-reliance on cars. We should continue to encourage walkable, transit-oriented urban growth that is accessible to all income levels, not unsustainable sprawl projects in high risk areas.

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST TO BE KEPT UP TO DATE ON THE LATEST IN SAN DIEGO LAND USE AND HOUSING ANALYSIS